早稲田大学 ジャーナリズム研究所 J-Freedom |

July 4, 2015

Power and journalism in “Jipang”:

From Galapagos to Rhodes

Tatsuro Hanada

(Director of the Institute for Journalism)

【(Image: Galapagos land iguana (Conolophus subcristatus)】

1

Seventy years after the end of World War II, journalism in Japan finds itself facing an inextricable crisis. In the post-war era, has journalism in Japan matured, or has it ultimately failed in its development? Has it developed independently, or has it been hijacked by other forces? Where did this crisis come from-what caused it, and is there a way out?

2

In the early 1830s, when Charles Darwin was in his twenties, he went on an expedition to the southern hemisphere on the survey ship HMS Beagle and observed plant and animal life there. Based on those observations, he later came up with the theory of natural selection. On the expedition, during his stay in the Galapagos Islands, he became fascinated by such animals as the Galapagos giant tortoise and the Galapagos land iguana. He found the remote Galapagos Islands to be home to a distinct biota featuring many indigenous species that had evolved uniquely. There were no large mammals on the islands to play the role of natural predator to those unique species.

【(Image: Charles Darwin)】

【Image: Leucosia anatum】

(The Leucosia anatum, or pebble crab, will turn on its back, stand upside down, or play dead when it senses the threat of a predator.)

3

I believe that if a modern-day HMS Beagle were to arrive at the island of “Jipang” and its passengers were to observe the society here, they would be fascinated by a certain endemic species not seen in other environments throughout the world. I call that species the “Jipang masscomi.”1 Because it shares some characteristics with the journalism species, the two are often confused, but are actually different creatures. The Jipang masscomi is somewhat unusual, in that when it runs into its natural enemy the leviathan, it attempts to survive by standing on its head. Eventually it became so used to standing on its head that today, it remains perpetually upside down, walking around on its hands. When upside down, its relationship to the predatory leviathan appears inverted, the opposite of what it actually is. To the leviathan, this situation is surely quite convenient, since its natural enemy, journalism, ceases to exist. Thus, in an environment remote from the rest of the world, the Jipang masscomi has aimed to use this fiction as a method of survival, and the species has managed to preserve itself up to the present.

【Image: Hippopotamus dolls standing on their hands】

【Image: Panel discussion】

(Enlarge flyer)

To the Jipang masscomi, this situation has become so natural that it remains unaware of its true state, but to the keen eyes of visitors from the outside, this social creature appears as a rare species that differs significantly from anything else found on planet Earth.

For example, in 2012, after the Great East Japan Earthquake, New York Times Tokyo bureau chief Martin Fackler released a book titled Credibility lost: the crisis in Japanese newspaper journalism after Fukushima. The book can be read as a modern-day version of Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle. I believe it serves as a record of observations of the behavior of the Jipang masscomi. On the last page of the epilogue, Fackler makes the following observation:

【Image: Martin Fackler’s book】

“The true victims of the press club system are not reporters for the foreign media like myself. Japan’s freelance reporters and those working for magazines and online news sites are impeded from collecting news materials freely. Young reporters working at major media outlets are unable to report on what they are interested in even if they hold journalistic aspirations. However, the biggest victim of the system is Japan’s democracy itself. The media involved in the press club system are failing to perform their role as watchdogs, and are failing to properly critiquing those in power.”2

“Why do Japan’s major media outlets fail to express more outrage? Looking at their reporting, even where criticism occurs, it feels somehow detached. If the media fails to arouse debate in society by criticizing those in power, a healthy democracy will never form.”3

I believe this is an accurate representation and assessment of the behavior of the Jipang masscomi toward the Jipang leviathan. I want to make particular note of the observation that “even where criticism occurs, it feels somehow detached.” This is actually one of the Jipang masscomi’s fascinating characteristics derived from its perpetual upside-down position.

Yet another outside observer has written about the Jipang leviathan’s recent aberrant behavioral patterns. Before leaving Japan at the beginning of April 2015, Carsten Germis of the German Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reflected on his five years as a correspondent in Tokyo in “On My Watch,” an article posted on the homepage of the Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan (FCCJ).

“The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung is politically conservative, economically liberal and market oriented. And yet, those claiming that the coverage of Abe’s historical revisionism has always been critical are right. In Germany it is inconceivable for liberal democrats to deny responsibility for what were wars of aggression. If Japan’s popularity in Germany has suffered, it is not due to the media coverage, but to Germany’s repugnance at historical revisionism.”

The above describes Germis’s position and the culture from which he comes. Yet Germis himself was apparently called a “Japan basher” by certain Ministry of Foreign Affairs bureaucrats and people affiliated with the Japanese media. He goes on to describe a peculiar and unusual experience.

“What is new, and what seems unthinkable compared to five years ago, is being subjected to attacks from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs - not only direct ones, but ones directed at the paper’s editorial staff in Germany. After the appearance of an article I had written that was critical of the Abe administration’s historical revisionism, the paper’s senior foreign policy editor was visited by the Japanese consul general of Frankfurt, who passed on objections from “Tokyo.” The Chinese, he complained, had used it for anti-Japanese propaganda.

It got worse. Later on in the frosty, 90-minute meeting, the editor asked the consul general for information that would prove the facts in the article wrong, but to no avail. “I am forced to begin to suspect that money is involved,” said the diplomat, insulting me, the editor and the entire paper. Pulling out a folder of my clippings, he extended condolences for my need to write pro-China propaganda, since he understood that it was probably necessary for me to get my visa application approved.”4

In other words, Germis testifies that the Jipang leviathan is attempting to render impotent journalists from foreign lands and force them to follow its rules, using intimidation to force these foreign journalists to stand on their heads just as it has done to the Jipang masscomi. We must not naively underestimate the Jipang leviathan. We must be fully aware that it is malevolent and willing to go to any ends to achieve its goals.

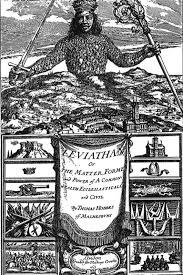

【(Image: The original Leviathan】 【Image: Leviathan in Japanese translation】

The above two outside observers view the media landscape of Jipang as something quite distinctive. I believe that system can be described as follows. With each handstand the Jipang masscomi does in order to evade a confrontation with its natural enemy the leviathan, the upside-down position comes to feel progressively more natural, and eventually became its habitual state. However, at some point the Jipang masscomi lost awareness that it was upside down, and could only see itself and its relationship with the outside world from a perspective detached from reality. This system most likely developed and took hold during the period of high economic growth starting in the 1960s. Its development was enabled by Japan’s isolated environment, separated from the rest of the world by the barrier created by the Japanese language, and fed by demand from a sizable domestic market requiring an equally large-scale Japanese-language mass media. This facilitated a unique evolutionary process leading to the emergence of the Jipang masscomi as a distinctive species peculiar to Japan.

I believe that politically, a joint editorial published in concert by all seven of Japan’s major daily newspapers in 1960 marked the beginning of the epoch. After a bill to approve a revised version of the U.S.-Japan security treaty was unilaterally rammed through the Diet by the Liberal Democratic Party, demonstrators opposing the bill surrounded the Diet building on a massive scale, where they clashed violently with police. A female university student was killed in the clash. Two days later, on June 17, all of seven of Japan’s major daily newspapers (Asahi, Mainichi, Yomiuri, Nikkei, Sankei, Tokyo, and Tokyo Times) published the same editorial on the front pages of their morning editions, titled “Joint Declaration: abandon violence and protect parliamentarianism.” Since the newspapers had previously criticized the government for ramming the bill through the diet, the joint editorial marked a sudden about-face. It could be understood as a collective ideological conversion on the part of the press, marking the beginning of a new era of conformism on the part of the media. The new security treaty was automatically approved in the Diet, followed by the resignation of the Kishi cabinet and the formation of the Ikeda cabinet. The Japanese government’s focus shifted to the economy, represented by Ikeda’s plan to double Japan’s national income. In that climate, Japan’s newspapers, broadcasters, and other media corporations developed into a branch of the dream industry referred to as the masscomi. Many media corporations were successful from a business perspective, and earned the status of top-tier companies, hiring from society’s elite. Inversely proportional to the business success of media corporations, the potential for serious journalism diminished, as Japan’s mass media developed into just that―a form of media for the masses and mass-media based journalism, namely masscomi.

【Image:Liviathan】

Furthermore, the Jipang leviathan has today managed to force all of its natural enemies to stand upside down, allowing it to behave in whatever despotic manner it likes, without even trying to hide its arrogance. Why has this occurred? Because nearly all of its natural enemies have disappeared. Since it is so close to being entirely unopposed, the Jipang leviathan is particularly annoyed by the two newspapers that inhabit the Ryukyu archipelago to its south. Those two newspapers, the Ryukyu Shimpo and the Okinawa Times, refuse to stand upside down, endeavoring to maintain their role as a watchdog of the powerful and an ally of the people, and to remain members of the journalism species, the natural enemy of the leviathan. In June 2015, members of the Liberal Democratic Party close to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe held a study session at the Liberal Democratic Party headquarters at which Okinawa’s two newspapers were criticized as biased, with one participant, a prominent supporter of Abe, going so far as to say that the two papers needed to be “crushed.” The Jipang leviathan revealed its true nature as a monster that aims to eliminate, crush, and destroys anyone who does not toe the line.

A political scientist would describe this as one step toward the formation of an authoritarian government. Japan’s current government denies political ideologies it does not and cannot understand, such as the idea of a social contract between civil society and the state, and the principle of constitutionalism that uses reason to constrain state power. The current administration differs fundamentally from the past conservative administrations Japan has seen. That an authoritarian government has lawfully come to power seventy years after the end of World War II undoubtedly reflects the current consciousness of the Japanese electorate. The development of such a social consciousness is simultaneously a product of the Jipang masscomi’s success and journalism’s weakness and failure. I would even call it a collapse of reason and enlightenment. During the bubble era in the late 1980s, intellectual play promoting hedonism and deriding reason and enlightenment as relics of a former era were in vogue, and that tendency may now be coming back to haunt us.

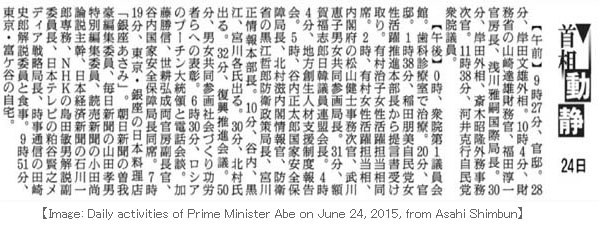

【Left image: Prime Minister Abe’s Facebook page on September 20, 2013】

(“Tomorrow is my fifty-ninth birthday. I received a present from the reporters assigned to cover me. No matter how old I get, it’s always nice to get a present.”)) https://www.facebook.com/abeshinzo/posts/410640509059398:0

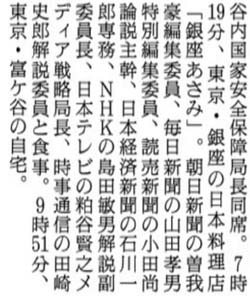

【Image: Close-up of an article detailing the prime minister’s daily activities on June 24, 2015】

4

Below is an unordered list of examples of the phenomenon to which I refer as the Jipang masscomi standing upside down.

- The press club system described by Martin Fackler above restricts participation in the process of transmitting public information, promoting collusion.

- The “Editorial Competency Statement” released by the Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association in 1948 stipulates that editorial competency lies with the media corporation’s executives and not with the reporters in the editorial department. This relic of the Cold War era has yet to be abolished.

- Editorial and executive functions remain undifferentiated.

- The term jishukisei (“voluntary restraint”) is used without compunction to disguise what is really self-censorship.

- Part of the Japanese mentality and character is that people endeavor to be considerate of others’ wishes by trying to speculate what others want and act preemptively in accordance. This is form of a personality structure inherited from the past in which one must not go against his or her superiors. Japanese people will attempt to speculate the wishes of bosses or company management, politicians, or the United States, and base their own actions on the assumed preferences of those parties. (This behavior is called sontaku in Japanese, and is widespread in the mass media sector nowadays.)

- Journalistic ethics are not determined or ensured by journalists themselves, but rather are decided from above by industry organizations based on suppositions of the wishes of those in power. In other words, ethics are established by those in the business side of the industry.

- The culture of Japanese media ignores those directly involved with news production. Judgements and decisions regarding ethical journalistic issues are outsourced to third-party organizations.

- The company is always prioritized and considered central. (Consider whether one is viewed as an employee of a newspaper company, or as a newspaper reporter or journalist.)

- The Japanese media is quite unusual in that there is hardly any space for freelance journalists.

- The mentality of editorial board members causes them to prioritize preservation of the company over the carrying out of journalism in times of crisis.

- Many people, especially those involved in the media, do not understand the significance of expression as a subjective act and how important independence is for journalists doing investigative journalism.

- Some newspapers promise their readers that they will put effort into investigative journalism, but in reality, investigative journalism is not published, and the only thing that grows is the paper’s corrections column.

- We see hardly any original investigative reporting by individual reporters. An increasing proportion of newspaper space is taken up by press club briefings, pre-packaged manuscripts, and outsourced manuscripts.

- Incompetent reporters band together to reject competent reporters. This is a classic example of a tight-knit society that excludes those who are different-“the nail that sticks up gets hammered down.”

- Management and executives of media companies and organizations do not protect journalists, reporters, or program producers, but rather defame and forsake them when a problem arises.

- There is a unique media culture in which slogans about freedom of speech and freedom of expression are repeated time and time again, but we hear only silence when it comes to the freedom and independence of journalists.

- Some media outlets cater and conform to the administration, become one with the ruling party, and form a coalition with the ruling coalition government. In other words, they stands firmly on the side of those in power.

- On the prime minister’s birthday, he was presented with a cake by female

reporters assigned to cover his daily activities.

- Male editors and executives join the prime minister for cozy conversation over food and drink in the evening.

- Additionally, another phenomenon appears to have emerged due to a contagion spread by the Jipang masscomi. We see species of commentators, critics, intellectuals, and experts in

journalism and masscomi studies whose livelihoods depend on journalism, but who are determined

not to possess, develop, or introduce5 any affinity for the basic tenets of journalism.

How are we to understand these perverse phenomena and culture?

In short, I believe the problem lies in the alienation of journalists, who in theory should be the bearers of the “ism” of journalism. Journalists ought to be the protagonists in the field of journalism, but have been thoroughly removed from their proper position in the field. In place of journalists we see a species of “masscomi worker” who turn a blind eye to the contradiction of their own existence, evade and ignore the problem, and ultimately deceive themselves to the extent that they lose sight of their own self-deception.

5

Is there a way to recover from this alienation? There is at least one, and it may be the only one. It is for the Jipang masscomi to stop walking around on its hands. It must return to an upright position and view the world as it is, rather than an inverted version of reality. It must aim to achieve its noble status as the Jipang leviathan’s natural enemy. That is the path to recovering journalism’s integrity. Journalists must regain a spirit of active participation. They must stop maintaining a sense of detachment when applying criticism. Journalism’s recovery depends on whether journalists can take on the historical role entrusted to them in the modern era as critics of state power with an active interest in their work, and whether that sense of active participation can form the basis of a journalist’s identity.

For some, this will require casting off a simplistic, innocent, gullible, childish, ignorant way of thinking--a naive perspective in regards to state power. For others, it will require casting off a love for the vulgarly ostentatious and an impulse to cater to those in power in an attempt to garner a share of the glory. In all cases, it will require bold confrontation with those in power, bolstered by self-respect and pride in the journalistic profession.

In one of Aesop’s Fables, when a traveler boasts of a great leap he once made on the Greek island of Rhodes, he is told, “Very well, imagine this is Rhodes, and show us your leap.” The story, called “The Leap at Rhodes,” advocates the need for hard evidence over empty rhetoric. Some say that the challenger’s question also implies, “If not here and now, then when, and where will you leap?” If a journalistic creed prompts one, as Naoyuki Arai has said, to “say here and now what must be said,” I would like to say the following right now to Japan’s journalism: “This is not Galapagos. This is Rhodes, so leap right here, right now.” It is impossible to leap with the resolution of an Olympic athlete when one is standing upside down on ones hands.

【Image: Running leap】 【Image: Leap】

At present, the only way forward may be to escape from the shackles of the masscomi, be reborn as an individual journalist, foster horizontal relationships, and aim to construct a network of individuals through communication, deliberation and dialogue. We then must not aim to accrue power for ourselves in the manner of the leviathan, but rather to separate ourselves from the seats of power, stand on the side of those who have been disadvantaged by the acts of the powerful, and become existential actors who pursue the truth through uncovering facts. This will require allies. Reporters confronting a mighty, iron-clad opponent must not be isolated, but must mutually support each other in professional solidarity. Organization is necessary to guarantee and ensure that solidarity. That Japan lacks a professional organization for journalists is also unique from a global perspective.

6

The Institute for Journalism is an attempt to be part of the solution. Our abilities are limited, but we are dedicated to taking small, concrete steps toward achieving journalistic freedom and independence, with the broader aim of reforming and innovating journalism from within.

Footnotes:

1. In Japanese, the term “Masukomi” (Masscomi) is used to refer to the media and journalism. The meaning of the term is very vague and difficult to define. Masscomi may seem to be a shortened form of the English phrase “mass communication,” but is not one in terms of meaning. I would say

【Image: Leap】

“Masscomi” is a the name of a real condition where the mass media (as a system) and journalism (as an activity carried out according to an “ism”) adhere to each other and do not find any conceptual separation in social functions, corresponding to the company-centered principle of the Japanese media sector.

2. Martin Fackler, ‘Hontou no koto’ wo tsutaenai nihon no shinbun (Futaba Shinsho, 2012), 220-221.

3. Ibid, 221.

4. Carsten Germis, “On my Watch,” http://www.fccj.or.jp/number-1-shimbun/item/576-on-my-watch.html (accessed July 4, 2015).

5. Translator’s note: This plays on Japan’s policy of the “three nonnuclear principles,” which state that “Japan shall neither possess nor manufacture nuclear weapons, nor shall it permit their introduction into Japanese territory.”

(For more detailed information about our activities, please visit the Institute for Journalism homepage. http://www.hanadataz.jp/ )

(English translation by Sandi Aritza)